“Just borrowing a story from Hollywood will not mean the film will be a hit. I need something in the film with the Indian roop (touch). Even in Punjabi videos, everything will be Western, they will be wearing jeans and shorts, but the dhol (drum) will be playing in the background, which is the essence of our civilization. I will always need that Indian touch in films.”

The Indian film industry, previously confined mainly to South Asia in its scope and resources, has evolved globally, attracting more significant international audiences and foreign investment. Since 2005, corporations such as UTV Motion Pictures, Eros International, and India Film Company, are included in trade on the London Stock Exchange and its Alternative Investment Market. The Walt Disney Company obtained a majority stake in UTV in 2011. On top of that, UTV and other Indian media companies have entered production and distribution agreements with global media conglomerates, such as the infamous partnerships between Disney and Yash Raj Films, 20th Century Fox and Dharma Productions, and Warner Bros. and People Tree Films. With the continued development of multiplex cinemas across India and the drive toward digital distribution, by 2024, overall revenues are expected to rise as high as 58.423 percent above 2021 figures. The Mumbai-based Hindi film industry alone has an overall revenue of approximately 1.5 billion dollars by 2021, even after the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on cinema.

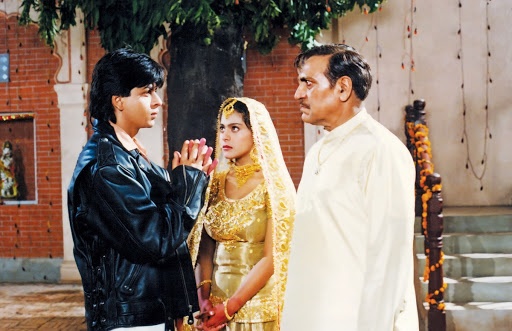

Alongside these market developments, Indian film narratives in scope have also become more global. Due to the rapid expansion of communication and economic networks between South Asia and its Diaspora during the 20th century, the complex relationships between Indians, Non-Resident Indians (NRIs), and their descendants have served as significant plot points in numerous feature releases. In the Hindi film industry—more commonly known as “Bollywood”—international hits like Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (Brave Heart Will Take the Bride, Aditya Chopra, 1995), Namastey London (Vipul Amrutlal Shah, 2007), Delhi 6 (Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra, 2009), My Name is Khan (Karan Johar, 2010), and Anjaana Anjaani (Strangers, Siddharth Anand, 2010) all have embraced the South Asian Diasporic experience as an essential element for romance, comedy, action, and melodrama.

According to Amit Rai, an Indian film director and writer, this shift in markets and storytelling has created a new tension in Hindi films. “It selectively sells a chauvinistic brand of national culture, thereby paying its debts to (Hindu) nationalism,” he explains, “while its financial and profit base is increasingly oriented toward the centers of capitalist accumulation in the West” Rai sees this as “a tendency of profit accumulation as much as ideological alignment”

Indeed, changes in markets and audiences for Hindi cinema on different narratives have contributed to new visual and discursive procedures to filmic space as an expression of South Asian identity. The developing geographical imperatives of characters and events scattered across South Asia, North America, Australasia, Europe, and beyond have challenged traditional hierarchies of exegetic and diegetic space of Bollywood storytelling, particularly in the location, arrangement, and discursive implications of the musical sequence. Films rooted in the Diasporic experience, for example, have decreased or eliminated the conventional meta-narrative role performed by musical arrangements held in Western settings by displacing these with South Asian sequences serving a similar purpose. Since musical sequences are regularly shot and launched before the finished film, they may continue to circulate as music videos on satellite television, the internet, and other media platforms long after audiences lose interest in the movie. Ultimately, becoming a critical component in representing the diaspora and shaping a Diasporic imaginary.

Musical arrangements from the 1990s to the beginning of the 21st century have established alternative visual frameworks of national and cultural inclusion, embracing both the diaspora and the effect of globalization on identity and the non-elite audiences in India. However, this global shift has separated the musical sequence from the narrative. For film producer Anustup Basu, contemporary arrangements “often seem to detach themselves from relations of fidelity to the filmic whole,” in what he calls “an ‘indifferent’ logic of ‘televisual’ production and dissemination.”

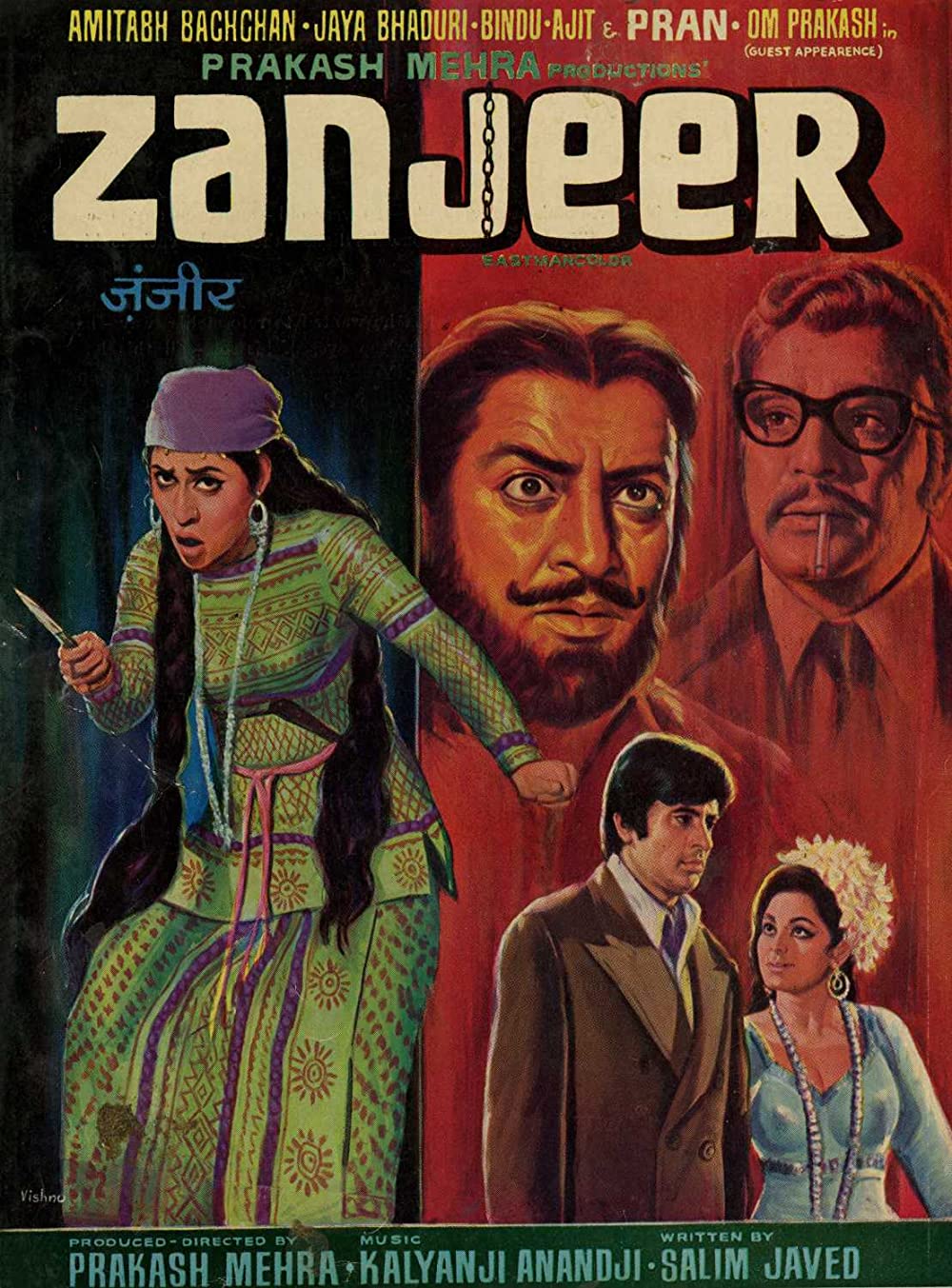

“Simply put, such sequences can arrive without any casual relation to the story,” Basu claims, such that “they can invoke bodies, spaces, and objects that can arrive from any visual universe whatever” While recognizing the probable polyvalence of musical arrangements acting outside the film narrative across different platforms and exhibition modes, this paper will argue against such distinct divisions. Instead, such seemingly inconsistent arrangements invoke glocalization within film narratives while serving the cinematic representation of the nation and South Asian identity in new ways. This essay will examine this transformation by analyzing the relationship between narratives in two hit Bollywood films produced between 1973 and 1995: Zanjeer, without musical sequences, and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, with musical arrangements.

According to most scholars, globalization has led to significant changes in the structure of media production and perception in South Asia. On the one hand, the process of globalization is expanding boundaries and, on the other hand, strengthening existing boundaries of culture, identity, and self. In short, people’s “perceptions of time and space” are changing due to globalization.

This article introduces and describes glocalization as an alternative to the typical international communication paradigm. Glocalization is epistemological, but its application to media studies is restricted. Globalization was presumed to represent Americanization and Americanization was not understood in local terms other than “western dominance”). Rarely did international communication include ethnographies or other reception studies that accounted for the diversity of international audiences, media practices, and consumption. Glocalization is best defined as international communication. The essential purpose of glocalization is to account for new cultural forms developing at the global-local interface. When ideas, artifacts, institutions, images, practices, and performances are transplanted, they bore the markings of history and undergo cultural translation. Glocalization must be understood as an encompassing process that, although located at national or subnational levels, involves transnational formations that “connect multiple locations in complex and contradictory ways.”

The emergence of Indian cinema paralleled the country’s fight against British colonialism. As a result, cinema has always played a key role in defining an Indian cultural identity in its “allegory, shape, and form. The Indian cinema industry was able to break free from the “shackles of Western influence” with the introduction of “talkies” in the early 1930s; language disparities provided “natural protection” to Indian producers Films were made in vernacular languages with a “profusion of songs”. The first Indian talkie, Alam Ara (1931), featured 12 songs and was advertised as “all talking, all singing, all dancing.” many of these songs were individually recorded and broadcast on the radio. The drama-music style drew on the lengthy heritage of the Ramayana and Mahabharata, two Indian classical Sanskrit epics whose narrative twists inspired cinematic storytelling.

Indian popular film evolved as “India’s sole model of national unity” with a focus on “realist aesthetics” after the end of colonialism. In the cinematic imagination, a tension between modernity and tradition, westernization and indigenousness, evolved. These dialectical conflicts gave rise to a unique conception of Indian identity. In the 1950s, directors like Raj Kapoor and Bimal Roy showed the underprivileged world by describing Indian society as “iniquitous and unequal.” In films including Awara (1951), Bandini (1963), Do Bigha Zameen (1953), Jagte Raho (1956), Shri 420 (1955), and Sujata (1959), the creators conveyed a sociopolitical message. In the 1970s, Hindi films served as catalysts for the nation’s homogenizing agenda, appealing to the disadvantaged by fostering faith in the “nation-protective state’s beneficence”. The underlying assumption was that the (poor) “angry, young man” was the primary audience of these films.

The tremendous success of Zanjeer (1973), a film about a police officer who works outside the bounds of the law, introduced the figure of the “angry, young man” to the Indian screen.

This hero is a disaffected, cynical, violent, rebellious, urban/worker who is often seen single-handedly fighting wealthy businesses and ineffectual and corrupt politicians. In Zanjeer and the evolution of the genre, the world of the “angry, young man” involved crime, unemployment, and poverty; articulating the anguish of the marginalized sector. It was a device through which Hindi films ensured viewer identification with the working poor and lower-middle-class audiences.

This idea is also present in Kumar Talkies, a documentary on what cinema means to people from small towns. Calling it the “slum’s point of view of Indian politics and culture … in the popular cinema, there is the same amount of stress on lower-middle-class sensibilities and on the informal, not-terribly tacit theories of politics and society the class uses.

The changes precipitated by the “liberalization of the Indian economy” throughout the 1990s facilitated the growth of the production and distribution of Hindi films. However, with the entry of satellite television, Indian filmmakers began operating in a new media landscape, where a vast range of options, including easy access to Bollywood and Hollywood films, was available to viewers at home. With liberalization, the financial equations in Bollywood changed too. Overseas distribution rights for a big-budget film roughly doubled in price compared to the Indian market. Television and music rights also generated more revenue than the entire production cost, even before selling a single ticket. The rise of multiplexes in large metropolitan cities (where the cost of tickets was ten times higher than the cost of tickets in family-owned, small-town theaters) increasingly focused film producers on niche audiences who “pay more, buy more” and needed to be reflected in the movie’s contents.

According to D’Souza, a film trade analyst, the days of the “silver jubilee are over.” He adds: “now films target small segments of primary filmgoers who constitute the paying public.” For D’Souza, the “paying public” not only can pay for the movie ticket but has disposable income and attracts advertisers.

Audiences also play a critical role in creating genres. Genres do not consist only of films: they consist also, and equally, of specific systems of expectation and hypothesis that spectators bring with them to the cinema. These systems provide spectators with a means of recognition and understanding. This recognition of a changing audience and Bollywood as an international cinema is increasingly articulated through musical passages exploring diasporic duality. Here, the ideological function of the film genre in shaping both viewer and product while making the process and relationship appear natural and reflective of the world as it is or ought to be is compromised. As the needs of audiences and markets threaten the traditional terms of national cinema, the changing role of the musical sequence reveals a tension between the recognition of demographic changes in the audiences for Hindi cinema and an effort to articulate nation and national identity.

In its effort to deliver a sense of national identity that inscribes the NRI through changing discursive operations, the convergence of Hindi cinema’s representational systems with the diasporic imaginary opens onto a third space, sometimes referred to as “Bollystan.” Bollystan, a neologism derived from the popular term for the Hindi film industry and the Hindi suffix for “place,” denotes a discursive space of mediated cultural overlap between India and the South Asian Diaspora. A- ranked films are popular in A centers: metropolises such as Delhi, Bombay, Madras, or Bangalore, as well as with NRI audiences overseas. B and C films play in small towns and villages as well as with lower-class viewers in tent theaters that cater to the urban poor. This is when recent Bollywood musical sequences attempt to preserve the ideological myth. It frequently reifies values such as chastity, piety, tradition, and familial duty, all typically displayed in the Western-oriented musical sequences of the All-India film, presenting them as latent but essential characteristics of the NRI, regardless of her specific everyday circumstances.

According to anthropologist Brian Keith Axel, the diaspora is “not strictly here, so much as it is here and there, or at least elsewhere.” Axel argues, “we come to understand Diaspora as something objectively present in the world today about something else in the past—the place of origin,” and “in searching for its context, we return our Diaspora home.” As emigration causes physical separation and psychological dislocation, the stability of the South Asian Diaspora becomes dependent on a fusion of West and East within a problematic identity split. The Bollywood narrative attempts to simplify the process by reducing it to an impossible, idealized separation of physical signs and mental states within the South Asian in the Western environment. The subject negotiates disparate cultural norms, creating the instability of a cultural hybrid of potential contradictions. An NRI bachelor imagines telling his ideal mate in 2007’s Namastey London, “I like one thing about you: your style is Western, but your mind is Indian.”

Through Hindi cinema’s relocation of exegetic musical sequences to South Asian settings, Bollystan can offer diasporic audiences a combination of South Asian and Western codes while reinforcing an underlying allure of India and its culture at home and abroad.

Indeed, one can argue that in the Diasporic turn of Hindi narrative and its impact on musical sequences, Bollystan emerges less as a utopia than heterotopia, both for the South Asian Diaspora and the increasingly urbanized and technologically mediated Indian middle class. Heterotopias are privileged spaces within a culture that serves “as a sort of simultaneously mythic and real contestation of the space in which we live.”

Earlier sequences set in Western hotels and bars as places of escape from inherited Indian values reflect his idea of contemporary “heterotopias of deviation,” where “individuals whose behavior is deviant about the required mean or norm are placed.”

Amid the complex relationship between the South Asian diaspora and Indian media and its impact on ideas of national identity, To reflect this “crisis heterotopia,” Jyotika Virdi, author, The Cinematic ImagiNation – Social History Through Indian Popular Films, has proposed a long-lasting “discourse of the nation within the transnational” in Hindi cinema. “The ‘fictional nation’ is central to all Hindi films,” she says. “The film obsessively portrays serious tensions that threaten to divide the country as moral conflicts or ethical quandaries. The central goal of Hindi film’s “national fiction” is to address these issues ” By realigning the musical sequence as a long-standing trope of unmarked space, the informal structures of nationally-focused narratives suggest the persistence of a more general South Asian cultural heterotopia across global networks and markets. The hybrid codes of Hindi cinema have the potential to become paradoxically reassuring signs of cultural stability and the “fictional nation’s” endurance. This illusory continuity, which has been manifested in several films since the mid-1990s, may appeal to diasporic dreams of a homeland and India’s increasingly cosmopolitan, middle-class populations who seek imagined stability of national origin and character in the Hindi cinematic tradition.

Over the last two decades, how has this shift manifested itself in Hindi cinema and its critical reception? Films such as Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge have received much attention for depicting the diaspora’s tense relationship with India and the role musical sequences can play in emphasizing or alleviating underlying cultural tensions. Musical sequences set in South Asia, particularly in rustic or traditional settings like farmyards, fields, and temples, represent a fantasy space where repressed and implicitly original Diasporic beings are revealed and celebrated. Such sequences depict India as a spiritual domain of inalienable national identity, capable of surviving the realities of modernization and migration. However, this contradicts claims that NRI-centered narratives portray the Indian diaspora as “preserving their cultural universe through Indian rites of passage in an alien Instead, South Asian musical sequences represent distant, imaginary spaces “alien” to the diegetic framework that such rites safely preserve. Musical interludes in this striking transformation, like Western sequences in older films, can still be read as transgressive or subversive, despite their ostensible rejection of Western values and culture.

The character’s changing physical traits and movements are crucial to these “transgressions.” According to author, Wimal Dissanayake, the performance of Bollywood musical sequences raises fundamental problems about identity and distinction. He asks, “How do the performing bodies enact their difference from themselves?” and “How do the bodies in dance sequences augment and subvert in non-dancing sequences?” Once upon a time, the stereotypical European metropolis or Western nightclub provided characters with brief opportunities to abandon native conventions and enjoy short dresses and rock and roll. However, modern films addressing the diaspora predicament may have a single South Asian scene. Miniskirts and jeans are frequently replaced by saris, kurtas, shalwar kameez, and dupattas. Westernized protagonists adorn themselves with South Asian cultural symbols. Dissanayake’s difference reveals an underlying unity of being in a South Asian spirit that is fundamentally irrepressible.

The sequence liberates the protagonists from the implied confines of so-called liberated Western clothing, hairstyles, and mannerisms, allowing a South Asian essence to play over and through their bodies, visually and ritualistically fusing physical and spiritual in front of the audience’s gaze. The depicted body quickly returns to its predominantly Westernized behavior and environments within the narrative. However, its subsequent actions can be interpreted as adaptation or mimicry rather than identity. As a result, much like the heterotopic mirror “that enables me to see myself there where I am absent,” the “non-dance body” is reinterpreted in the musical sequence’s counter-representation. This process is gender-biased, favoring female characters over male characters, and follows the pattern of Indian cinema. According to Majumdar, “the burden of nationalist representation” has fallen on female characters in narratives referencing the West as the “pure site of the superior traditions of the East” Nonetheless, the process extends to male characters, as shown in the examples below.

Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (DDLJ), a seminal film in its treatment of Diasporic subjects in Western and South Asian spaces, marks the beginning of this discursive transformation of the musical sequence. Raj and Simran are portrayed in DDLJ as college-aged children of NRIs living in London. Simran, engaged to the son of a family friend in India, begs her father to allow her to travel through Europe with her schoolmates during the summer. “I’m going to live in a country I don’t know, marry a man I’ve never seen,” she explains. “There won’t be another chance. I don’t even know if I’ll ever return.” She meets Raj while Eurailing in the Alps and falls in love with him. However, she is dragged away to Punjab upon returning to England for her wedding. Raj follows her and ultimately thwarts the marriage by disrupting the wedding preparations and gaining her parents’ approval.

The story of DDLJ takes place in three geographical locations: Great Britain, the Alps, and India. Although all three are thoroughly interwoven into the diegesis, the Alps serve as a narrative hinge with several functions. As the protagonists travel by train and automobile across this countryside, it preserves remnants of the unmarked site of escape accumulated in Hindi films since the 1960s. In the “Zara Sa Jhoom” (Let Me Dance a Little) segment, for instance, Simran rolls in the snow in a short, sleeveless red dress, the height of Western nightclub fashion, accompanied by a combination of tabla drums, violins, and trumpets. Simran, who was often reserved, had spotted the dress in a store window and thrown a rock through the plate glass to steal it. This occurrence is essential to the larger plot. Outside of the Alps, the places of Britain and India remain fixed geographical endpoints for the story’s diasporic conflict as the challenges of familial obligation and cultural conformity bounce between them. Zanjeer lacks DDLJ’s fragile mystification of the West as a destination of escape and daily experience, a defining moment in Hindi film. As Bollywood storylines have progressively inhabited these Diasporic spaces, successive films have offered a more significant opportunity for securing the South Asian musical sequence’s position as the principal exegetical setting. However, this alteration threatens the status of unmarked space.

Despite their various depictions, recent films focusing on the South Asian diaspora emphasize the necessity of a return to the Indian subcontinent, if only through the virtual threshold of film, to effectively articulate Diasporic identity. In contrast to earlier Hindi films, such as Zanjeer, where living in India was a central narrative motif, modern Hindi cinema has confined this subject to the musical segment. Characters—and the viewers who identify with them—travel for only a few minutes, frequently in scenes devoid of expository connection with the story’s more significant spatial and chronological elements. This juxtaposition of narrative imagination and physical reality, as fictional characters dance in the natural fields of Punjab or stand in front of the monuments of Uttar Pradesh, sublimates both Indian and Diasporic desires. As Diasporic and South Asian audiences contend with the growing effects of westernization and glocalization, the physical locations of India are portrayed as exotic, tradition-laden environments.

In both Zanjeer and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, the intricacy of Diasporic and non-Diasporic concerns of identity and national values is evident. As the generic hybridity of Bollywood films remains a defining characteristic of its cultural specificity, the industry has found new ways to utilize this quality in order to address concerns of cultural hybridity within South Asian diasporic culture. In today’s internationally networked digital media environment, where transnational adaptation has revolutionized the means of ideological transmission of national cinema, the evolution of Hindi film is an important event. Despite considerable changes in Bollywood audiences due to mass international migration, growing urbanization, economic affluence, and media globalization, projected cultural uniformity is maintained through the musical sequence’s mutations in terms of Hindi cinema’s generic hybridity. In this shared region of Bollystan, anyone might find safety, knowing that its presence, however fictitious, indicates a stable identity with its Indian touch, even as Bollywood acquires a larger global audience.