This is one of the last scenes of Bollywood movie Krantiveer.

The protagonist – a role played by Nana Patekar – is delivering an emotional and fiery speech before a large crowd gathered to witness his public execution. This speech does miracles. It shakes the crowd out of its slumber and kicks off a revolution of sorts.

When Krantiveer hit the cinemas in 1994, social media was non-existent and electronic media had not reached its prime. This was probably the reason why the director of the movie had to get the hero to deliver a speech from the gallows in order to awaken the people.

However, newspapers, recording devices, and projectors were still quite popular at that time and these were the tools that the director of the 1989 movie Main Azaad Hoon used to spark an uprising.

In this film, a newspaper reporter creates a fictitious character, Azaad, who allegedly aired his grievances over corruption and social inequalities in imaginary letters addressed to the journalist. She later convinces a homeless person to pass himself off as Azaad in front of people in order to give credence to her claims. That homeless person – Amitabh Bachchan – later starts identifying with the ideology of the imaginary Azaad and becomes a revolutionary figure.

This film also ends with an inspirational speech, which the protagonist had recorded before committing a sacrificial suicide. The video of this speech is projected on a giant screen in a stadium packed with people, who ultimately rise against the status quo while singing a revolutionary song. These two movies, however, are not the only Bollywood flicks, in which heroes rather conveniently manage to mobilize masses for a cause. In fact, after the rise of TV channels, Indian film directors found a more helpful tool.

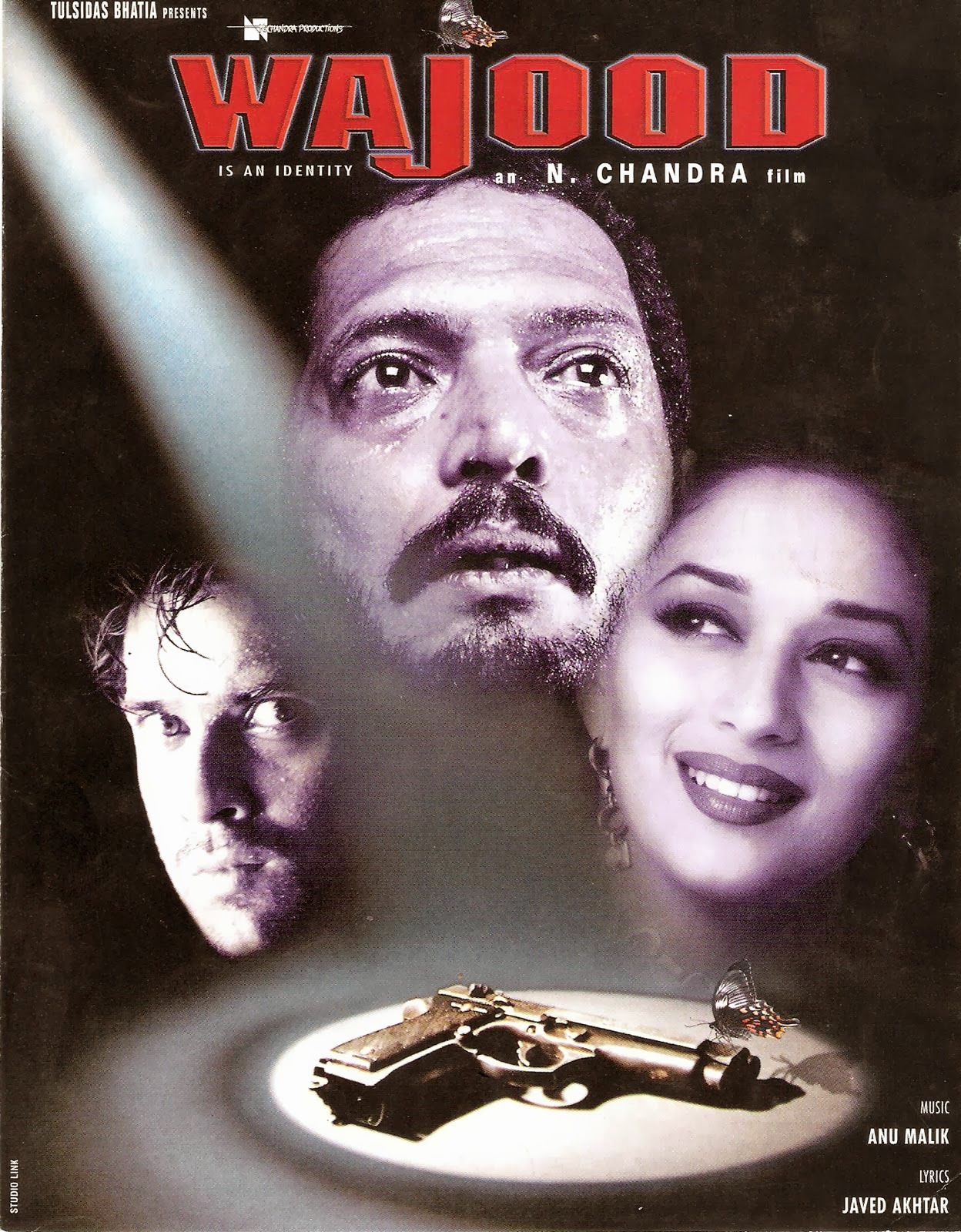

In films like Nana Patekar’s Wajood (1998) and Shah Rukh Khan’s Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani (2000) the protagonists use the electronic media – the television – to mould public opinion and mobilize public support. Interestingly, one of the protagonists in Wajood and both the hero and heroine in Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani are TV reporters. The latter movie also ends on a sort of regional uprising sparked by a video in which a death row convict exposes the crimes of some politicians and their cohorts.

In Anil Kapoor starrer Nayak (2001), the power of media rises to such a level that a TV anchor becomes the head of a state and that too as a result of a wager that he makes with a corrupt chief minister during a live television show.

In Ajay Devgan’s 2008 movie Halla Bol, the protagonist’s mentor shakes the conscience of the media in an interaction outside a hospital where the protagonist is fighting for his life. The media later embraces the protagonist’s cause and mobilizes the public in large numbers.

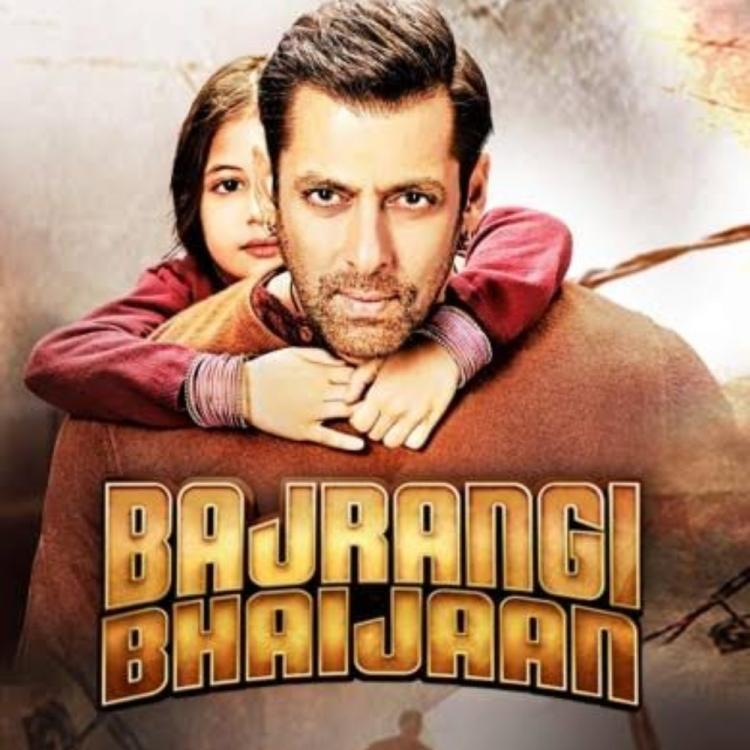

However, with the rise of social media, the process of rallying people around a cause got easier. In Salman Khan’s Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015), we once again meet a journalist, Chand Nawab, who instead of relying on traditional TV channels, uploads a video on YouTube and the whole Pakistani nation falls in love with the protagonist in a matter of hours.

In Aamir Khan’s 2017 movie Secret Superstar, YouTube takes on the responsibility of turning an unknown girl into a superstar in a matter of days.

Television channels may have awakened some people and social media platforms may have created some superstars. However, these Bollywood movies want us to believe that a message – particularly the one delivered through traditional and social media – has the power and impact like a bullet. These films seemed to be based on the rather outdated Magic Bullet Theory which postulates that a message broadcast over airwaves acts like steroid injections and has the power to immediately convert people.

This idea – also called Hypodermic Needle Theory for obvious reasons – was largely discredited after the rise of scientific research in Mass Communication by the 1940s.

Later, research showed that mass media doesn’t influence in this simplistic manner and media messages can’t be directly injected into the brains of a passive audience. Every message has to go through a number of filters and a lot of factors determine its impact.

Ideas, ideologies, beliefs and attitudes of people don’t change in the blink of an eye. You can deliver any message through mass media but only a minority of people respond to it in a desired manner.

However, Indian filmmakers’ faith in the power of media and their belief in peoples’ willingness to accept every message doesn’t seem to have even slightly shaken.

They still think that last words from the gallows, investigative reports, sting operations and viral videos can bring about a social change; can rouse people from slumber; can spark a revolution.

That is probably the reason why India has the greatest number of TV channels in the world, one of the biggest film industries, and a huge presence on social media platforms.

However, this tendency of Indian directors to infuse media with this extraordinary power to rally people around a cause may have sprung from their concept of “Human”.

According to Muhammad Hasan Askari, the Man – Admi – is an imperfect and unruly being full of unexpected shortcomings and weaknesses.

On the other hand, the Human – Insan – is a concept created by the “rulers” to manage and control the Man and Askari includes artists, thinkers and philosophers in the category of rulers. These rulers desire that “the Man” may turn into “the Human” so that they could manage him with greater ease.

If we can borrow terms from Askari, we can say that the rulers of India feel threatened by the divergent and clashing views, contradictions and unpredictability of its 1.38 billion “Men”. They feel that these unmanageable “Men” can lead India to disintegration and desire to turn them into manageable “Humans” who could be converted to any view just with a single message. One can respect this wish but cannot stop wondering if Bollywood can keep India unified with films like Kashmir Files. Only time and the BJP can answer this question.