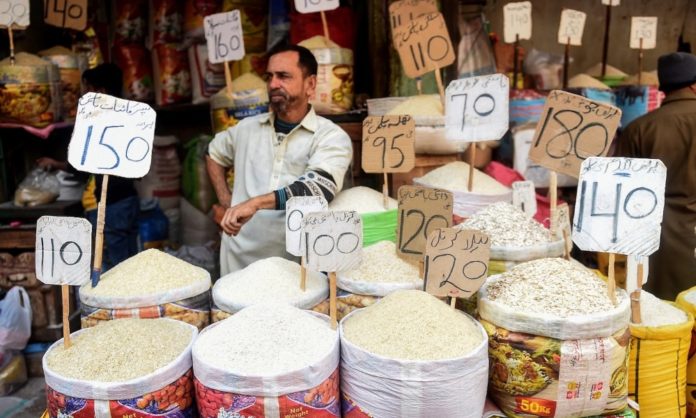

The price of roti has gone up from Rs12 to Rs15 apiece in my neighbourhood. That’s a 25 per cent increase within a month. The price of a can of potable water has risen from Rs80 to Rs100, which shows a 25pc monthly increase. The per-page photocopy cost is now Rs5 instead of Rs3, showing a 66pc increase in just one month. The price of a haircut at the barbershop in my middle-class area went up last month to Rs200 from Rs150, reflecting a hike of 33pc.

What’s going on?

Economists call it inflation. For normal people, it’s a sharp decrease in the purchasing power of their money. It’s the worst kind of ‘tax’: the prices of everyday items are increasing at a far more rapid pace than their incomes.

The mental agony it’s causing is more hurtful. It’s getting difficult to put food on the table for even those people who earned enough income until now to make ends meet rather comfortably. A lot of parents I personally know have pulled their kids out of school in order to save the two-month tuition fees. Perhaps they think they’ll be able to afford the education of their kids when schools reopen in August after the summer break. Chances are that education will become more expensive by then. Inflation is just picking up the pace, and it’s likely to get a lot worse.

Going by official statistics released by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, the consumer price index (CPI) rose 21.3pc on a year-on-year basis in June. The estimate sounds understated if you’re the one buying groceries and paying bills in your household. But for the sake of this piece, let’s stick to official numbers, which are horrifying in their own right.

Transport expenses alone went up more than 62pc on a year-on-year basis in June. Food became dearer by almost 26pc. The increase in the prices of perishable food items was more than 36pc. A lot of the increase in food prices usually originates from the rising cost of transportation. It’s safe to assume that the full impact of the fuel price hike hasn’t been passed on to consumers yet. So brace yourselves for another month of an unusual surge in food prices.

The 21.3pc year-on-year increase in the CPI, which is the most commonly used measure of inflation, has been the highest since December 2008 — the period when the world economy was in the throes of the Great Recession.

On a month-on-month basis, the increase in the CPI was 6.3pc, a multi-decade high. What happened in June? That was the month the new coalition government relented before the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and allowed electricity and retail fuel prices to go up by 52pc and 37pc, respectively.

Transport expenses alone went up more than 62pc on a year-on-year basis in June. Food became dearer by almost 26pc. The increase in the prices of perishable food items was more than 36pc. A lot of the increase in food prices usually originates from the rising cost of transportation. It’s safe to assume that the full impact of the fuel price hike hasn’t been passed on to consumers yet. So brace yourselves for another month of an unusual surge in food prices.

Inflation is a worldwide phenomenon. Energy-exporting Russia invaded food-producing Ukraine in February this year and caused unprecedented disruption to the global energy and food supply chains. The supply chain shock caught everyone by surprise. But not every country has reacted like the proverbial deer caught in the headlights. Sure, no country can predict the unpredictable. But preparing for a so-called Black Swan – an unpredictable economic event with severe consequences – is very much possible.

Countries with intelligent leadership build buffers, plan contingencies and maintain a war chest to survive through unanticipated events like these. Have we been preparing for such an eventuality? Not at all. In fact, it may surprise you to learn that 24 million out of the total 30 million consumer connections in Pakistan were receiving electricity at subsidised rates until recently, according to former central bank governor Dr Ishrat Husain. In other words, every eight of 10 electricity connections received subsidies regardless of whether they deserved it or not.

Doling out untargeted subsidies in good times always results in forced belt-tightening in bad times. We built no buffers when we could spare the resources. Now we find ourselves in the middle of global inflationary pressures and a commodities super-cycle with no cushion for contingencies.

It’s times like these when governments usually opt for heavily subsidising the poor. They launch temporary work schemes so that people can earn enough money to sustain themselves in a dignified manner. They expand welfare programmes to take care of the weak segments of society. However, the government is working in the exactly opposite direction. It’s scaling down schemes like Sehat Card. It’s eliminating all subsidies on electricity consumption. It’s imposing more and more taxes on businesses and individuals.

Of course, the government is doing so at the behest of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which is extending a $6 billion loan to help Pakistan override its severe balance-of-payments crisis. But the result is the trampling of the micro by the macro. Economic indicators may see an improvement under IMF-directed belt-tightening, but only at the cost of hundreds of thousands of people who are slipping into the poverty trap every month.

The government must act now to mitigate the severe impact of inflation on the general public. The first step should be a renegotiation of a renewed loan programme with the IMF, which isn’t front-loaded. This means the negotiators should seek funds from the IMF in the immediate term but promise fiscal reforms after the commodities super-cycle is over. This will give the government some space to lessen the impact of high inflation through targeted subsidies.

In the medium-to-long term, however, the government should try to build a stronger, robust economy that can withstand systemic shocks like the global pandemic and commodities super-cycle.